By Nathan Briant, BBC South Online

Oxford City Council

Oxford City CouncilHuge changes are planned for the way motorists get around Oxford.

Oxfordshire County Council proposes to trial six traffic filters from November, for example.

They would restrict how many times people living outside the city can drive into it – though there would be 17 types of free permits. Critics include the transport secretary Mark Harper.

Then there are the arguments about low traffic neighbours, the zero emissions zone expansion across Oxford city centre, and the planned workplace parking levy.

But these difficulties are not new.

How the city’s motorists get around – or don’t get around, as the case may be – has caused friction for decades.

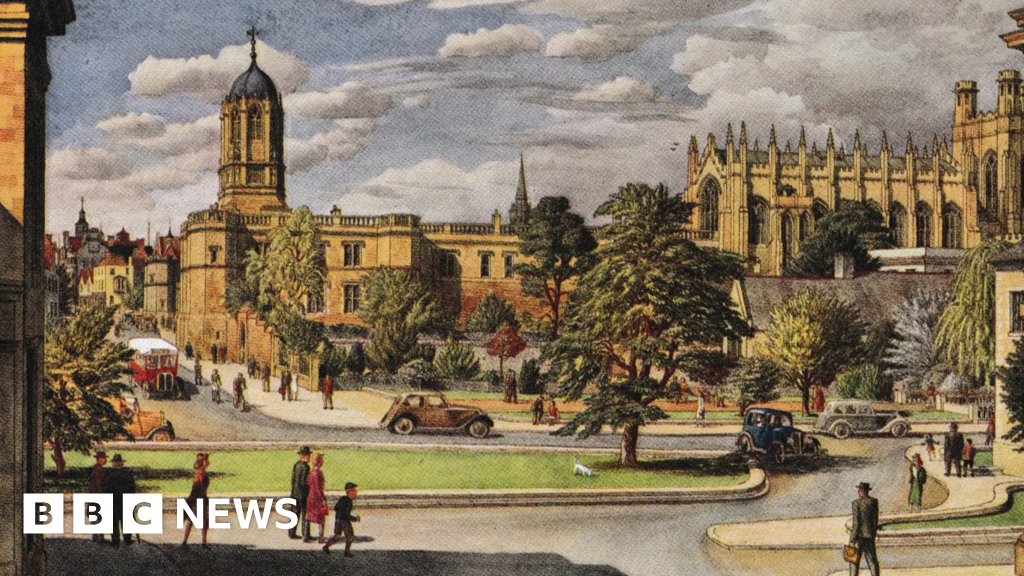

In 1945 radical town planner Thomas Sharp was commissioned by Oxford City Council to come up with new transport solutions.

Two decades of increasing car ownership had changed the city, and his Oxford Replanned report was published in 1948.

Oxford City Council

Oxford City Council In it, referring to the city’s “town and gown” divide, he said: “I am neither pro-town, pro-gown, pro-dungaree, nor pro- any other special interest at all (nor, indeed, anti- any interest): I am…quite simply pro-Oxford.”

His report found that what was “once an urban paradise” had become, in part, a “crowd of islands surrounded by vehicular torrents”.

But he said he could not “deal with all the 1,001 things that need to be done to make Oxford a better city”.

So he limited himself to 52 recommendations. Some arguably now look at best unwise, while others are just outdated.

He recommended a new location for Oxford’s cattle market, something that eventually closed in 1979.

Other suggestions, like giving “careful attention” to building heights to protect views of the city’s Dreaming Spires, are still useful today.

Oxford City Council

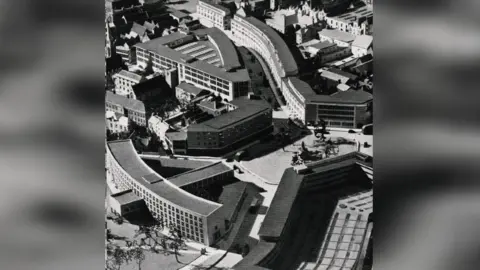

Oxford City CouncilThe most unpopular of his suggestions was surely a new road through Christ Church Meadow to relieve traffic across the city centre.

That debate ran for decades but ultimately ran out of steam in the early 1970s, when Oxford’s first park and ride was opened at Redbridge and bus lanes were introduced on some major roads.

The illustrations of the possible new road across the meadow look quaint now – a handful of vehicles trundling to a calm island at the bottom of a reimagined St Aldate’s.

What Sharp had imagined was a safe traffic management system that would have helped ease congestion and improve access to the city.

Oxford City Council

Oxford City Council But many would surely agree today that the cost of that to the city’s landscape would have been too great.

Sharp also suggested that for “the city’s well-being and its historical character”, Lord Nuffield’s car plant and pressed steel works in Cowley should have been moved “to some other part of the country”.

Though he wasn’t especially happy about them being in Oxford, Sharp felt the factories’ location in the south-east of the city was “in a place where they do as little harm to the physical amenities as any large factories can be expected to do”.

Part of the Cowley site is home to BMW’s Mini plant, which today employs about 4,000 people.

Getty Images

Getty Images Sharp also said Oxford’s population should have been limited to 100,000.

It would have “preferably” fallen to “90,000 or slightly less”, according to Oxford Replanned.

At the 2021 census, the city’s population was about 162,000, up from about 151,900 in 2011.

Sharp seemed not to like bikes a great deal – significant in a city where thousands cycled, and continue to cycle, every day.

“These [bikes in Cornmarket Street], and the 24,000 two-wheeled vehicles that are propelled over Magdalen Bridge in a single day, cannot be lightly dismissed as a number of mere bicycles. A few locusts are of little importance. A swarm is a plague,” Sharp said.

Oxford City Council

Oxford City CouncilHe argued Oxford had too few shops, too few hotel rooms and was on the way to becoming a “kind of minor English Detroit” (the pre-Motown Detroit of car manufacturing, that is).

Sharp said it was a “pretty safe gamble to bet” that Oxford had “less than half the number of shops” which most county towns had in the 1940s.

He looked in despair at the number of hotel rooms available. Stratford-upon-Avon had more, despite its population of just 11,500.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the nearly 80 years since the report was published, Oxford Replanned shows that, for all that has changed, the city is still battling with the same fundamental issue: how to move around a relatively small area while preserving its world class university and its architecture.

After all, his very first recommendation noted Oxford’s character is a “matter of national as well as local concern”.

“The future of the city must be settled in the light of its place in the national economy, and not merely out of a consideration of the internal needs of Oxford alone or out of the desires of the majority of its inhabitants,” he said.

Sharp died in Oxford in 1978, aged 77. At the time of his death lived in Farndon Road, in the north of the city.