University of Oxford

University of OxfordTiny radar chips are being fitted to bees to track their movements.

A team at The University of Oxford have been investigating how to help declining insect and bird populations.

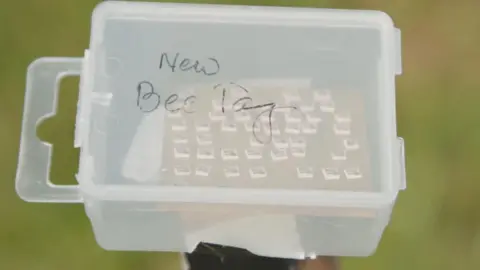

The new Biotracks technology tracks the harmonic radar tags attached to bees with a receiver carried on a drone in a bid to improve understanding of what is happening to pollinators.

Team leader Dr Tonya Lander, from the university’s department of biology, said they are hoping to share the equipment with other researchers.

University of Oxford

University of OxfordIt has been found that more than 85% of plant species are insect pollinated but 40% of insect species are at risk of extinction.

“That means if they don’t receive pollination, they’ll set fewer or possibly no seeds, which means no fruit for us to eat but also no reproduction of those plants for the next generations,” Dr Lander said.

In a video for the university’s website, the team said there was an “urgent” need to locate insects, monitor behaviour, follow local movements and track swarm migration.

“We have a radar transmitter sitting on the ground, a small tag attached to the back of the bee in between where the wings attach like a little rucksack and a receiver that’s carried on a drone flying up above,” Dr Lander explained.

Speaking to BBC Radio Oxford, she said they “ended up inventing the smallest harmonic radar tag ever” so that the insects could carry it without affecting their behaviour.

Other challenges included the amount of weight and the kind of equipment that could be safely carried on the drone.

University of Oxford

University of OxfordA small circuit attached to the radar system converts signals into a higher frequency, which is then picked up “with a very sensitive receiver”.

“It illuminates the bee, then pings back a higher frequency signal, which we can locate with another radio receiver,” said Associate Prof of Engineering Science Chris Stevens.

Prof Stevens described tracking small insects with radar as an “engineer’s extreme sport”.

“Because it was so difficult. Biotrackers have been able to make it a working technology, a real technology that we can use today,” he said.

He said its benefit was that the tracking range could be extended from a few metres “to potentially an entire field”.

Dr Lander said the team had just put the technology in action but had not yet “moved to the stage of actually doing the biology”.

“Great things to come but we’re at that transition point now,” she said.

University of Oxford

University of Oxford